Background: Most patients with cancer have multiple comorbidities and are at high risk of polypharmacy. In addition, reviews have shown that up to 33% of ambulatory patients with cancer are at risk of drug–drug interactions.

Objectives: To evaluate the polypharmacy risks and the impact that pharmacist assessments can play in a multidisciplinary supportive oncology clinic.

Methods: In this retrospective review, all patients who were referred to and attended the supportive care clinic from its initiation in June 2010 through May 2012 were assessed by a pharmacist. The risks for polypharmacy were assessed utilizing the AACME (Access, Adherence, Continuity of Care, Medication Reconciliation, and Education) method, which included evaluation for duplicate therapy, drug interactions, lack of efficacy and undertreated conditions, side effect causal relationships, and untreated conditions.

Results: Of 153 patients evaluated during the first year of the clinic, 69 patients (45.1%) were found to have some form of therapeutic duplication within their medication list, 54 patients (35.3%) had documented drug interactions, and 127 patients (83%) reported side effects that were attributable to 1 or more of their medications. Despite this, most patients (88.9%) reported uncontrolled symptoms, and a majority of patients (68.6%) reported symptoms that had not been previously treated.

Conclusion: These data suggest that, when evaluated by a pharmacist, the rates of polypharmacy risks may be higher than the rates currently published in the literature. It is possible, however, that this is an overestimate resulting from the complexity of the patient population evaluated. It is therefore likely that the true value lies somewhere between the values already published and what was seen in this analysis. Background: Most patients with cancer have multiple comorbidities and are at high risk of polypharmacy. In addition, reviews have shown that up to 33% of ambulatory patients with cancer are at risk of drug–drug interactions.

Objectives: To evaluate the polypharmacy risks and the impact that pharmacist assessments can play in a multidisciplinary supportive oncology clinic.

Methods: In this retrospective review, all patients who were referred to and attended the supportive care clinic from its initiation in June 2010 through May 2012 were assessed by a pharmacist. The risks for polypharmacy were assessed utilizing the AACME (Access, Adherence, Continuity of Care, Medication Reconciliation, and Education) method, which included evaluation for duplicate therapy, drug interactions, lack of efficacy and undertreated conditions, side effect causal relationships, and untreated conditions.

Results: Of 153 patients evaluated during the first year of the clinic, 69 patients (45.1%) were found to have some form of therapeutic duplication within their medication list, 54 patients (35.3%) had documented drug interactions, and 127 patients (83%) reported side effects that were attributable to 1 or more of their medications. Despite this, most patients (88.9%) reported uncontrolled symptoms, and a majority of patients (68.6%) reported symptoms that had not been previously treated.

Conclusion: These data suggest that, when evaluated by a pharmacist, the rates of polypharmacy risks may be higher than the rates currently published in the literature. It is possible, however, that this is an overestimate resulting from the complexity of the patient population evaluated. It is therefore likely that the true value lies somewhere between the values already published and what was seen in this analysis.

Most patients with cancer have multiple comorbidities and are at high risk of polypharmacy. In addition, previous reviews have shown that up to 33% of ambulatory patients with cancer are at risk for drug–drug interactions.1-3 A small percentage of patients (approximately 8%) have also been shown to be at risk for receiving duplicate therapies.4 The published data show that risk of drug interactions increases with the number of medications a patient is taking and increased age.4,5

Pharmacists are uniquely trained in medication therapy management, and a thorough medication therapy review can assist other disciplines in their assessments and interventions.6 It may be especially useful to have an oncology-trained pharmacist (ie, specialty oncology residency training or several years of practice in the field of oncology) in this setting, so that they could further integrate the patient’s cancer treatment with symptom management.7,8

Patients receiving multiple medications must be evaluated for both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. In a retrospective study of 4 centers evaluating 160 patients, 91% of those patients were prescribed at least 1 drug that was a substrate for, inducer of, or inhibitor of 1 of the 5 cytochrome P450 isoforms leading to clinically significant drug–drug interactions in 21% of those patients.3 These patients are not only at risk of drug interactions between their routine noncancer medication and their antineoplastics, but also with their supportive care medications and with medications that they were already receiving before they started treatment.

It is important to assess for polypharmacy in patients who are prescribed several drugs concurrently for the treatment of 1 or more coexisting diseases. A good example is a patient who may have been prescribed a benzodiazepine for an underlying anxiety disorder and is then given another benzodiazepine for anticipatory nausea. Polypharmacy occurs when patients are treated by multiple providers.9

It is often difficult for oncologists to manage an underlying chronic disease and its treatments along with the daunting task of treating the cancer and its accompanying symptoms. One of the best solutions today is improving communication and the involvement of multidisciplinary teams that include a pharmacist.

At St Luke’s Mountain States Tumor Institute, patients with complex physical and/or psychosocial issues are referred by providers to a multidisciplinary symptom management clinic. Patients are requested to bring in their medications so that the pharmacist can review them in full detail with the patient and confirm actual medications and their doses. Recommendations based on the medication reconciliation are provided to the supervising nurse practitioner, who determines the ultimate plan based on input from the entire supportive care team, which includes a dietitian, a social worker, a registered nurse, and a chaplain on a consultant basis.10

The findings of a supportive care clinic pharmacist assessment are outlined here. The objectives of this article are to evaluate polypharmacy risks in oncology patients and to evaluate the impact that pharmacist assessments can have on a multidisciplinary supportive oncology clinic.

Methods

All patients who were referred to and who attended the supportive care clinic from its initiation in June 2010 through May 2012 were assessed by a pharmacist. Patient demographics were collected on all patients, including visit date, referring physician, cancer type, and the number of medications taken at the time of the clinic visit (divided into scheduled and as needed). Medication therapy management visits conducted by the pharmacist followed the AACME (Access, Adherence, Continuity of Care, Medication Reconciliation, and Education) method.10,11 Using this model, the pharmacist documented all assessment findings that were discussed during a patient visit in the electronic medical record. Data documented in the medical record were collected and summarized, and assessment notes helped to isolate the main issues discussed with the pharmacist in these visits. In addition, the total time that the pharmacist spent with the patient was recorded.

Within the assessment, some parameters were based on patient report, the pharmacist’s clinical judgment, or both. Parameters based on patient report included insurance or cost issues, transportation issues, self-reported missed doses, and adverse effects. Parameters based on the pharmacist’s clinical assessment included the presence of duplicate therapy, clinically relevant drug–drug interactions, lack of efficacy, side effect causal relationships, and untreated conditions.

Duplicate therapy was defined as any unintended duplication in therapy for a single symptom or disease state and/or 2 medications in the same class (for example, 2 benzodiazepines or 2 short-acting narcotics). Drug interactions were assessed by inputting the patient’s complete medication list into the Micromedex 2.0 Drug Interactions checker, and were cross-checked with the Lexicomp Lexi-Interact online drug interaction analysis program. All major pharmacokinetic drug interactions were recorded, and pharmacodynamic interactions were recorded if they required intervention by the pharmacist.

Results

Between June 2010 and May 2012, 153 patients were seen in supportive care clinics conducted on different days across 4 clinic sites. All patients were seen by the same pharmacist to maintain consistency in clinical evaluation. Most patients were referred by a medical oncologist or medical oncology nurse practitioner (94%), although some referrals were received from radiation oncologists.

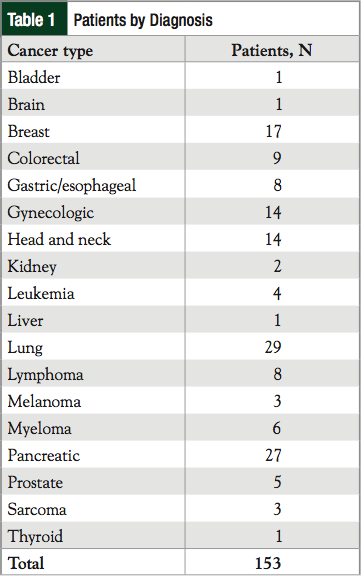

The most frequent diagnoses were lung, pancreatic, breast, gynecologic, and head and neck cancers (Table 1). The most frequent issues (found in >20% of patients) discussed with the pharmacist included constipation, depression, fatigue, medication-related questions, nausea, pain, and sleep. The average time spent with the pharmacist was 44 minutes (range, 15-90 minutes).

With regard to access, 60 patients (39.2%) reported cost issues mostly related to high copays and lack of insurance coverage for certain medications. A total of 37 patients (24.2%) reported transportation issues, and 61 (39.9%) reported issues with healthcare access. A total of 94 patients (61.4%) reported adherence issues and noted missing at least 1 dose of their routine medications in the past 2 to 3 months, with the most frequent reason being forgetfulness; however, confusion about medications and a lack of desire to take medications also played a role.

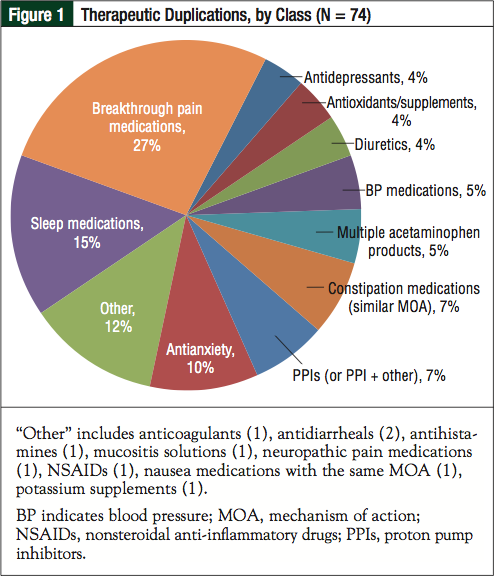

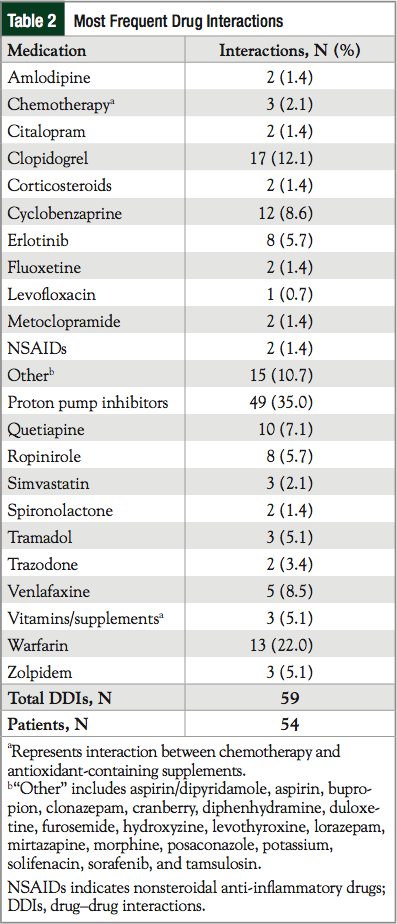

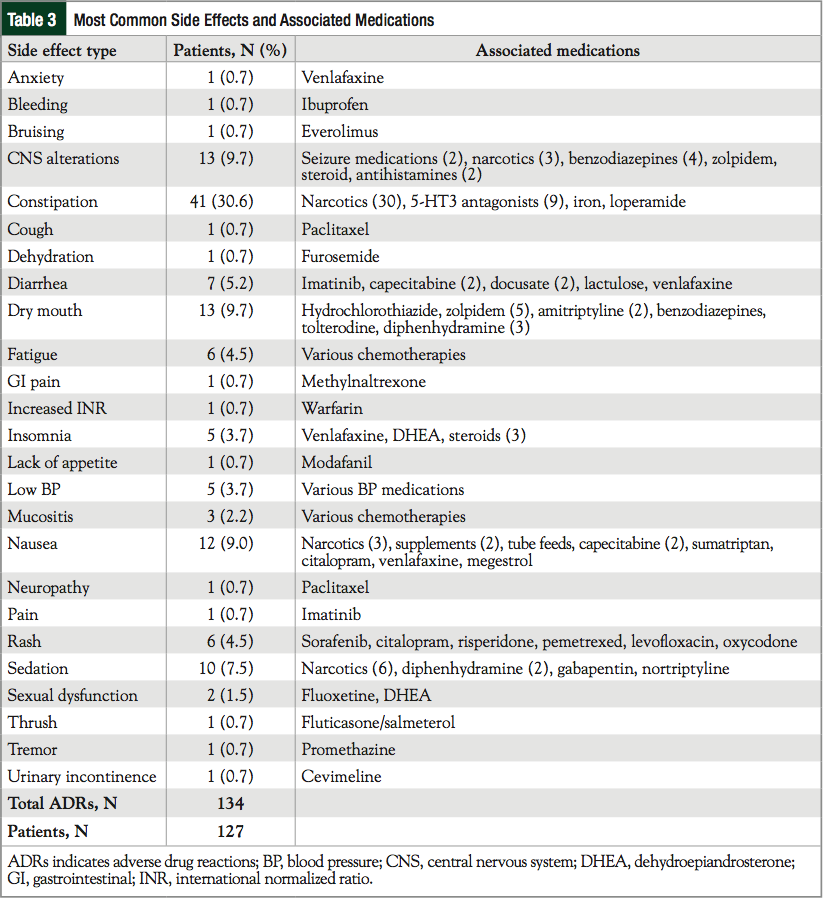

The medication reconciliation demonstrated the incidence of polypharmacy in these patients. Of the total patients, 74 (48.4%) were found to have some form of unintentional therapeutic duplication within their medication list (Figure 1), 54 patients (35.3%) had documented clinically relevant drug–drug interactions (Table 2), and 127 patients (83%) reported side effects that the pharmacist attributed to 1 or more of their medications (Table 3).

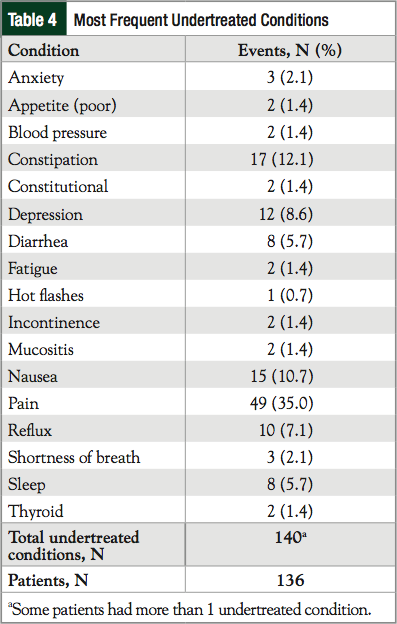

Despite this, most patients (88.9%) reported uncontrolled symptoms (Table 4), and a majority of patients (68.6%) reported symptoms that had not been previously treated (Figure 2).

Discussion

To date, the literature has shown that polypharmacy is a real risk to patients with cancer. A large part of this is a result of the fact that oncology is a specialty service, and thus patients, especially older patients, have multiple providers that they have seen for months to years before ever seeing their oncologist. As a result, patients enter the realm of cancer care with multiple medications well before their oncologist starts prescribing treatment-related medications.

Before this intervention, many patients have never had their medication list evaluated in full because of the use of multiple providers (eg, family medicine, surgeons, oncologists, other specialists).5,9

These data have shown that when evaluated by a pharmacist, the rates of polypharmacy risks may be higher than those currently published in the literature. It is possible, however, that based on the patient population evaluated, this may be an overestimate resulting from the fact that these patients were often getting treated for cancer which was complicated by or in turn complicated their other chronic disease states. It is likely that the true value lies somewhere between the values already published and what was seen here.

The unique aspect of our study is the evaluation and correlation of clinically relevant side effects related to medications, or, in other words, pharmacodynamic interactions. Previous studies have not examined the impact of how certain medications may compound symptoms in patients receiving active treatment for cancer.

Problems often arise from medications started for primary preventive measures that, because of shifting treatment goals, may no longer be needed (eg, cholesterol or blood pressure medications).12

In our evaluation, 83% of patients reported side effects that could be directly attributable to their medications, many of which were not their cancer treatments. In addition, extended time with a pharmacist has allowed discussions of each medication in detail with the patient. This helps to isolate undertreated conditions and the reasons for them. For example, perhaps a patient is fatigued, but he or she is taking a thyroid medication with food, and therefore a thyroid-stimulating hormone level is taken and found to be subtherapeutic. Or perhaps a patient’s pain is out of control, but he or she is only taking a long-acting pain medication as needed. Hence, some undertreated conditions or side effects can be resolved with education on proper use rather than increasing doses or changing medications. These issues may not be able to be evaluated fully in the limited time that oncologists have with their patients, and, therefore, referrals to pharmacists can help the oncologists focus on treatment-related issues.

Conclusion

We agree that pharmacists who have completed general and oncology specialty residencies or who have equivalent practice experience would be best equipped to fill this type of role.7,8,13 A background in general medicine, coupled with the specialty training or extensive practice in oncology, gives a pharmacist a unique ability to integrate all aspects of the patients’ care into this type of assessment. This background may also be why our study has been able to realize an increase in polypharmacy risks compared with those previously shown in the literature and provide more in-depth assessments.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Mancini is on the Speaker’s Bureau for Millenium Pharmaceuticals and has received consultant fees from GlaxoSmithKline. Ms Clifford has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

1. Riechelmann RP, Del Giglio A. Drug interactions in oncology: how common are they? Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1907-1912.

2. Riechelmann RP, Zimmermann C, Chin SN, et al. Potential drug interactions in cancer patients receiving supportive care exclusively. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:535-543.

3. Wilcock A, Thomas J, Frisby J, et al. Potential for drug interactions involving cytochrome P450 in patients attending palliative day care centers: a multicentre audit. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:326-329.

4. Riechelmann RP, Tannock IF, Wang L, et al. Potential drug interactions and duplicate prescriptions among cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:592-600.

5. Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status

for cancer, 1973-1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94:2766-2792.

6. van Leeuwen RW, Swart EL, Booms FA, et al. Potential drug interactions and duplicate prescriptions among ambulatory cancer patients: a prevalence study using an advanced screening method. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:679.

7. Watkins JL, Landraf A, Barnett CM, Michaud L. Evaluation of pharmacist-provided medication therapy management services in an oncology ambulatory setting. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2012;52:170-174.

8. Clinical pharmacists in oncology practice. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:172-174.

9. Lees J, Chan A. Polypharmacy in elderly patients with cancer: clinical implications and management. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1249-1257.

10. Mancini R. Implementing a standardized pharmacist assessment and evaluating the role of a pharmacist in a multidisciplinary supportive oncology clinic.

J Support Oncol. 2012;10:99-106.

11. Kliethermes MA, Schullo-Feulner AM, Tilton J, et al. Model for medication therapy management in a university clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:844-856.

12. Lord S, Hall PS, Seymour MT. Concomitant medications in cancer patients: should we be more active in their management? Ann Oncol. 2010;21:430.

13. Mancini R. The role of oncology pharmacists in the care team: chemotherapy management and supportive care at St. Luke’s Mountain States Tumor Institute. Oncol Pract Manag. 2012;2:16-19.